Category: war diary

-

A Scenic Walk from Ditchling Beacon to Wolstonbury Hill

On a bright summer’s day, we set off from the Ditchling Beacon car park for a delightful walk through the rolling hills and meadows of the South Downs. This route offered a mix of stunning chalk grassland, vibrant wildflowers, and breathtaking views—perfect for nature lovers and hikers alike. Starting at Ditchling Beacon Our journey began…

-

23&me leak

As of my last knowledge update in June 2024, 23andMe experienced a significant data breach in October 2023, where hackers accessed sensitive user information. Here’s what we know: What Happened in the 23andMe Breach? 23andMe’s Response Is 23andMe Still Compromised? What Should You Do? Long-Term Concerns Would you like help checking if your data was…

-

Amazon complaint

It sounds like you’re frustrated with Amazon’s lack of response to your formal communication. Here are some steps you can take to escalate the issue effectively: 1. Try Amazon’s Official Customer Service Channels Again 2. Social Media Escalation 3. Executive Escalation 4. File a Formal Complaint 5. Legal Action (If Warranted) Template for Follow-Up Email…

-

Collagen rich recipes

If you’re looking to boost your collagen intake, incorporating collagen-rich foods into your diet is a great way to support skin, joint, and gut health. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the body, and eating foods that contain it (or promote its production) can help maintain elasticity, reduce wrinkles, and strengthen connective tissues. Here…

-

Abbasid 10c recipes

The Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE) was a golden age of Islamic culture, and Baghdad, its capital, was a center of culinary innovation. The cuisine of Abbasid Baghdad was influenced by Persian, Mesopotamian, and Mediterranean traditions, featuring rich spices, meats, fruits, and grains. Here are some authentic recipes inspired by historical Abbasid-era dishes, drawn from medieval…

-

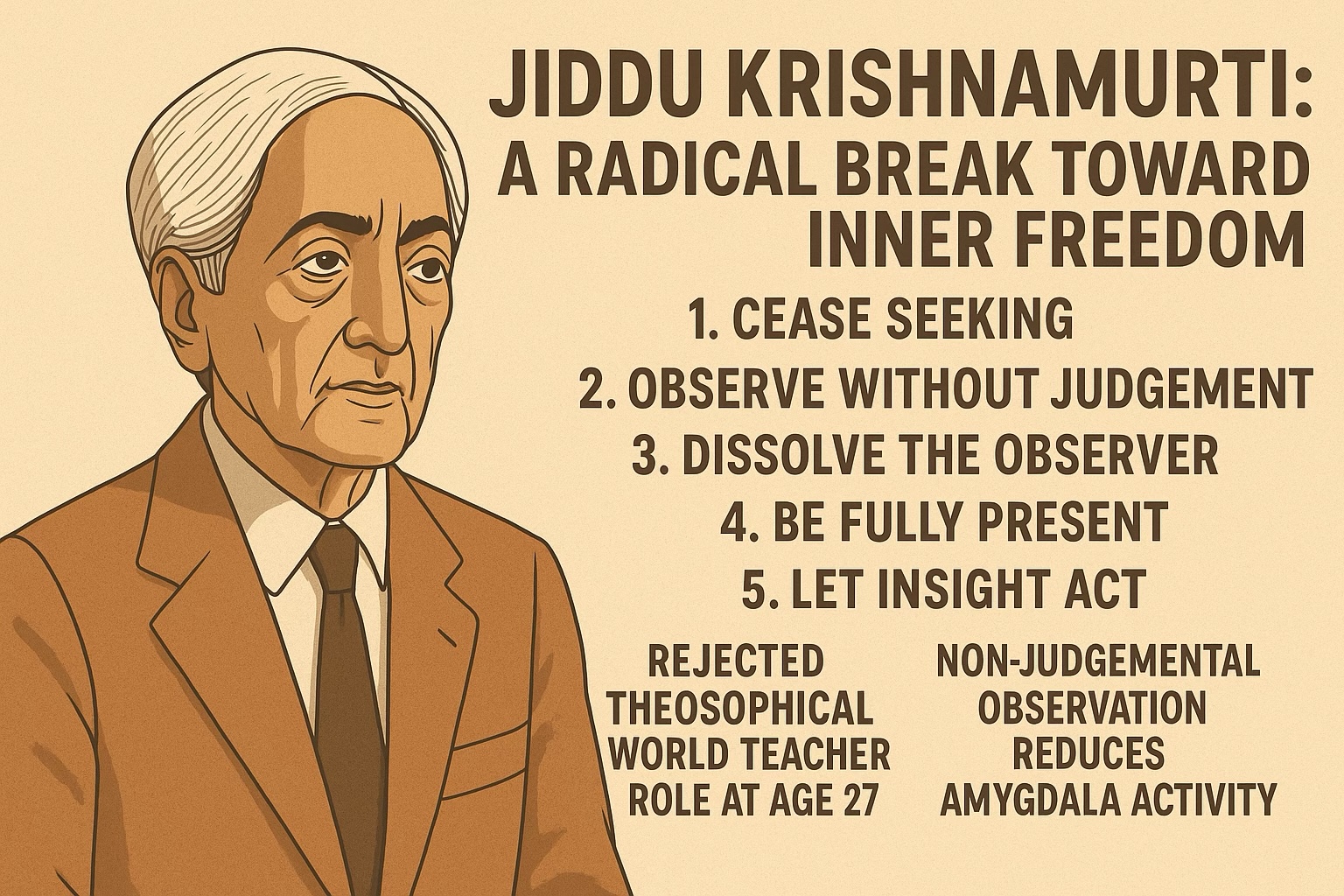

Jiddu Krishnamurti: A Radical Break Toward Inner Freedom

In 1929, at just 27 years old, Jiddu Krishnamurti made a decision that stunned the global spiritual community. After being groomed from age 14 by the Theosophical Society to become the “World Teacher”—a messianic figure expected to lead humanity into a new spiritual era—Krishnamurti publicly dissolved the organisation formed around him, the Order of the…

-

Analysis of “The Great Blood Pressure Scam” Blog Post

Overview of the Post The blog post, authored by A Midwestern Doctor, challenges the mainstream medical approach to high blood pressure (hypertension). It argues that hypertension is often misunderstood, overdiagnosed, and overtreated, with a focus on symptom management (lowering BP) rather than addressing underlying causes. The author suggests that high BP is more a compensatory…

-

Sunscreen and Skin Cancer: Is the Sun Protection Narrative a House of Cards?

Below is a blog post inspired by the X thread by Zaid K. Dahhaj and the related web search results, focusing on the topic of sunscreen, sunlight exposure, and skin cancer prevention. The tone is informative, thought-provoking, and encourages readers to rethink conventional advice while grounding the discussion in scientific studies and natural health perspectives.…

-

Fermented onion shampoo

DIY Hair Growth Shampoo Recipe with Onion Juice and Essential Oils If you’re looking for a natural way to boost hair growth, reduce thinning, and improve scalp health, this DIY shampoo recipe is for you! Inspired by the latest insights into natural hair care remedies—like the onion juice method shared by Dr. Eric Berg—this recipe…

-

Reviving Whites with Chemistry: The Potassium Permanganate Method

In an era where sustainability and innovation intersect, even the simplest household tasks are being reimagined through the lens of chemistry. A recent X post by @interesting_aIl has sparked curiosity and conversation about an unconventional method for whitening yellowed or stained white clothing using potassium permanganate. This approach, while not new, offers a fascinating glimpse…

-

Fight Dental Plaque Naturally: A 3-Ingredient Remedy You Can Try at Home

Dental plaque and tartar buildup are common struggles for many of us. Brushing twice a day with fluoride toothpaste is a great start, but sometimes stubborn tartar—a mineralized fortress of bacteria—needs a little extra help. A recent X thread by @DailyUpgrades_ (posted today, May 31, 2025) has gone viral for its simple 3-ingredient remedy to…

-

Barefoot Induction

The time needed to get used to barefoot shoes varies depending on factors like your current foot strength, activity level, and how quickly your body adapts. Here’s a general timeline and tips for a smooth transition: Typical Adaptation Timeline: Tips for a Smooth Transition: Signs You’re Adapting Well: ✔ Less foot fatigue✔ Better balance and…