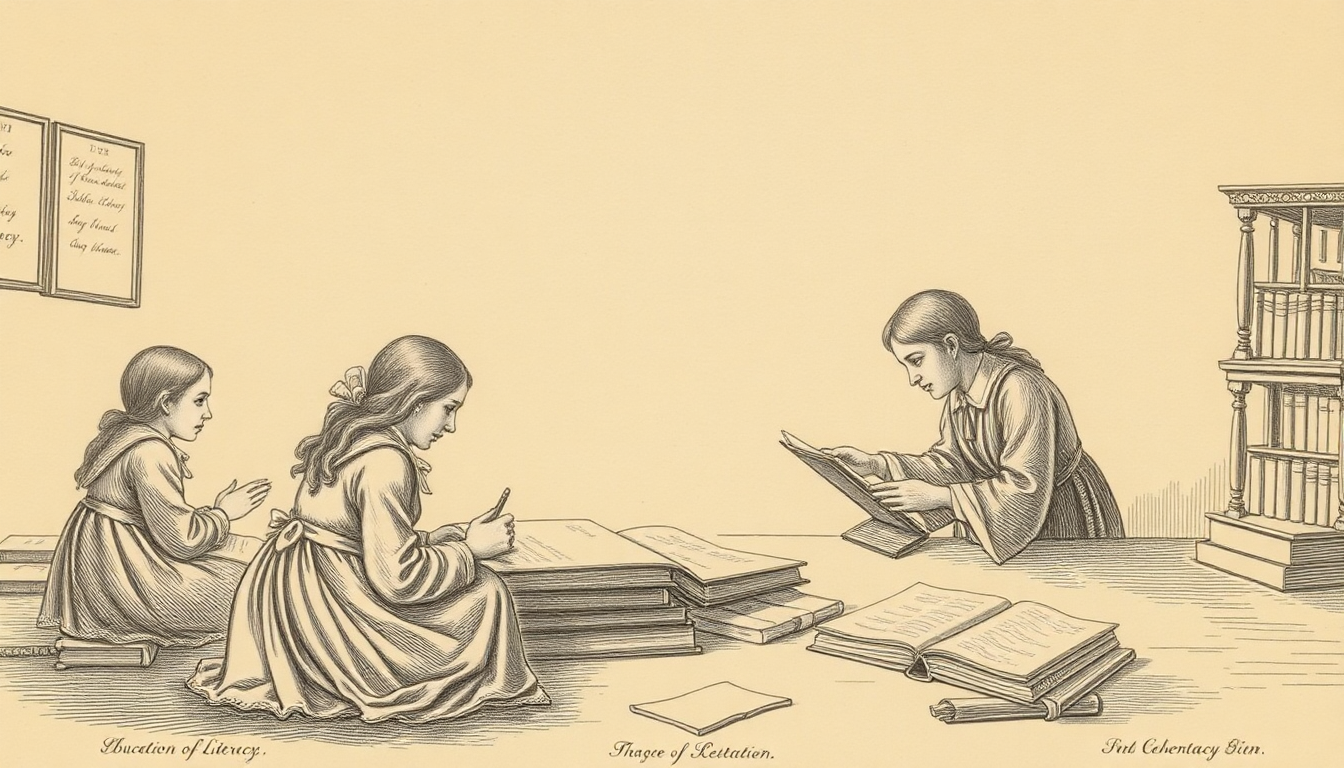

Education in 18th century England varied greatly depending on social class and gender. This chapter explores the different educational opportunities available, as well as the state of literacy and reading habits during this period.

Schooling for Boys

For boys of the upper and middle classes, formal education was more common. Dr. Samuel Johnson’s concern for his servant’s education provides an insight:

His sincere regard for Francis Barber, his faithful negro servant, made him desirous of his further improvement, that he now placed him at a school in Bishop’s Stortford, in Hertfordshire.

William Holland mentions his son’s schooling:

About 4 o’clock a chaise came from Bridgwater and my wife and I with Margaret and the two Miss Lewis went off. We reached Mr. Jenkin’s school some time before the play begun.

Education for Girls

Education for girls was often more limited and focused on domestic skills. However, some families provided more comprehensive education. Penelope Hind recalls:

Rarely did we return without finding marks of the tender way our Mother employed herself during our absence. At one time a little room allotted to us, and where we deposited our choices things, was fitted up afresh; pretty boxes Etc. of her own making to ornament, fresh prints to adorn it.

Universities and Higher Education

University education was primarily for wealthy young men. Dudley Ryder’s diary provides insights into student life:

Mr. Porter told me he wondered that I did not study physic for my diversion, it is a very pleasant and delightful study and proper to begin it with anatomy. That I might go and hear lectures upon bodies every month in the winter at Surgeons Hall in Wood Street twice a day about 1 and 5 in the afternoon.

Apprenticeships

For many young people, especially from the lower classes, apprenticeships were a form of education. Dr. Claver Morris mentions his apprentice:

Jack [Apprentice] ran away from me when I began to chastise him for absenting himself from dinner-time till candlelighting from my business in the Elaboratory.

Reading Habits and Literacy

Reading was a popular pastime for those who could read. Nancy Woodforde often mentions reading in her diary:

I have spent the latter end of this month in walking, reading “The History of England” and making shirts for Uncle.

However, literacy rates varied greatly across social classes. James Lackington, a bookseller, notes the difference in literacy between classes in Scotland:

There are in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Stirling etc. more real fine women to be found than in any place I ever visited. It must be obvious that in making this declaration I allude to the genteelest part, for among the lower classes of women in Scotland, by being more exposed to the inclemency of the weather, the majority are very homely and the want of the advantages of apparel together with their sluttish and negligent appearance does not tend in the least to heighten their charms.

Letter Writing and Correspondence

Letter writing was an important part of education and social life. Mary Delany was a prolific letter writer:

I am glad your rebuke to the postmaster has been of use to you; nothing can be more provoking than having letters kept from one; Your letters are just one week coming to me; what makes them so tedious?-I used to have your letters from Gloster the third day.

Self-Education

Many people, particularly those without access to formal education, engaged in self-education. Dudley Ryder’s efforts to improve himself are evident:

Read several Spectators … One of them was to expose the very trifling affections and inclinations of the fair sex, that are affected chiefly with outside of persons and distinguish them rather by their equipage, habits, etc. than the solid virtues of the mind and endowments of the understanding.

In conclusion, education in 18th century England was far from universal or standardized. While formal schooling was becoming more common, particularly for boys of the upper and middle classes, many still relied on apprenticeships, self-education, or informal instruction. Despite these limitations, the period saw a growing interest in education and literacy, laying the groundwork for the educational reforms of the 19th century.