- Dr. Zoe Harcombe clarifies that LDL and HDL are not cholesterol but lipoproteins that transport cholesterol and other lipids in the blood, criticizing the oversimplified “good” and “bad” cholesterol labels often used by medical professionals.

- She highlights the misuse of terms like LDL-C and HDL-C interchangeably with LDL and HDL, emphasizing that cholesterol (C27H46O) is the same molecule in both, challenging the narrative that cholesterol itself is inherently good or bad.

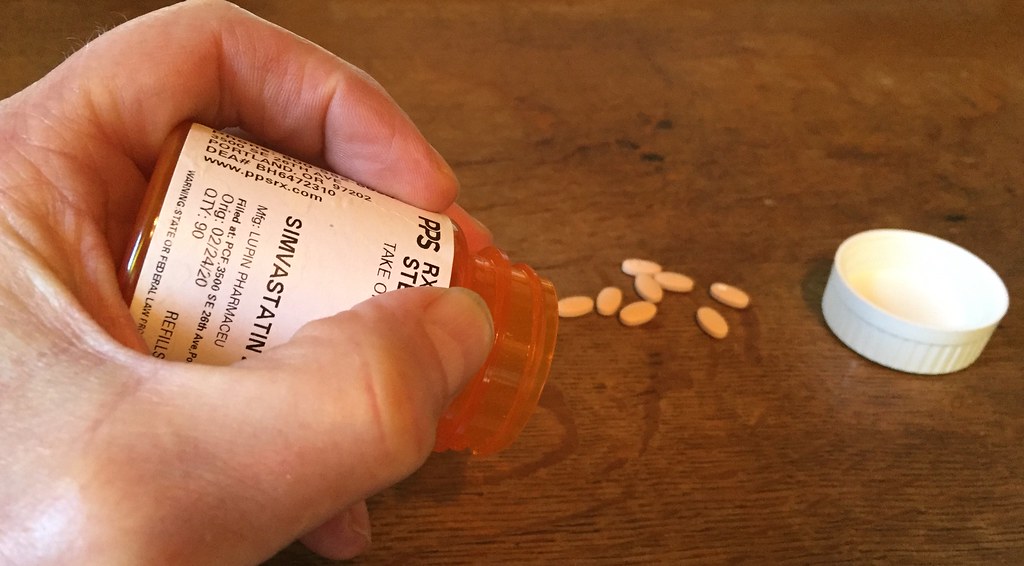

- Harcombe suggests that the focus on lowering cholesterol, often through drugs like statins, may be driven by financial incentives, aligning with critiques of the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on medical guidelines, such as the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines that expanded statin use.

It looks like you’re asking for a blog-style analysis or summary of the X post by Dr. Zoe Harcombe, PhD, which you provided (Post ID: 1918996726062493722). I’ll craft a blog post that breaks down her rant about LDL, HDL, and cholesterol, while also weaving in insights from the related posts, web search results, and some additional context to make it engaging and informative for readers interested in health, nutrition, and medical science.

Debunking Cholesterol Myths: A Deep Dive into Dr. Zoe Harcombe’s Rant on LDL, HDL, and the “Good” vs. “Bad” Narrative

Published: May 5, 2025

If you’ve ever been told you have “high cholesterol” or been prescribed statins to lower your “bad cholesterol,” you’re not alone. For decades, cholesterol has been painted as a villain in the story of heart disease, with LDL (low-density lipoprotein) often labeled as “bad” and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) hailed as “good.” But what if this narrative is oversimplified—or even outright misleading? That’s exactly what Dr. Zoe Harcombe, PhD, argues in her fiery X post from May 4, 2025, where she breaks down the science of lipoproteins and challenges the cholesterol dogma that’s dominated medical advice for years. Let’s unpack her rant, explore the reactions it sparked, and dig into the broader context to see what’s really going on with cholesterol.

The Core of Dr. Harcombe’s Argument: LDL and HDL Are Not Cholesterol

Dr. Harcombe starts by setting the record straight: LDL and HDL are not cholesterol. They’re lipoproteins—think of them as taxis that shuttle cholesterol, triglycerides, proteins, and phospholipids around your bloodstream. LDL-C refers to the cholesterol carried by LDL, and HDL-C is the cholesterol carried by HDL. The problem, she points out, is that people—including doctors and academics—often use “LDL” and “LDL-C” (or HDL and HDL-C) interchangeably, which muddies the waters.

Her analogy of lipoproteins as taxis is spot-on and aligns with what we know from biology. According to the Cleveland Clinic (web ID: 1), lipoproteins like LDL and HDL transport lipids to cells in your body. LDL delivers cholesterol to tissues, while HDL is often described as a “garbage truck” (as user Brent R puts it in a reply) that ferries excess cholesterol back to the liver for processing and elimination. But Harcombe’s key point is that the cholesterol molecule itself (C27H46O) is identical whether it’s in an LDL or HDL particle. There’s no such thing as “good” or “bad” cholesterol—only good or bad misunderstandings.

This isn’t just semantics. Harcombe argues that labeling LDL as “bad cholesterol” and HDL as “good cholesterol” oversimplifies a complex system and fuels a narrative that may not be as evidence-based as we’re led to believe. In fact, she suggests that the focus on lowering cholesterol is “eye-wateringly lucrative,” hinting at the financial incentives behind cholesterol-lowering drugs like statins.

The Financial Incentives Behind Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs

Harcombe’s jab at the profitability of cholesterol-lowering drugs isn’t a conspiracy theory—it’s grounded in reality. Statins, which are prescribed to lower LDL-C levels, are among the most widely used medications globally. A 2005 meta-analysis cited in the web search results (web ID: 2) showed that statins can reduce the risk of myocardial infarction by about 30%, which sounds impressive. But as the same source notes, their population-level effectiveness is limited due to underprescribing, non-adherence, and other factors. This has led to aggressive pushes to expand statin use, such as the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines, which lowered the threshold for prescribing statins and sparked debate about overmedication.

The replies to Harcombe’s post echo her skepticism. User @Leighlines shares a personal story, saying, “The handing out of statins like smarties is disastrous. My father is recovering after being put on the strongest one on the highest dose.” Meanwhile, @johndmtb raises a valid concern: “When you know that your brain makes cholesterol then perhaps taking cholesterol-lowering drugs doesn’t sound like such a good idea.” They’re right—cholesterol is essential for brain function, cell membrane structure, and the production of hormones like cortisol and sex hormones, as well as vitamin D (web ID: 0). Overzealous lowering of cholesterol could have unintended consequences, a point often glossed over in the rush to prescribe.

Harcombe’s critique also ties into historical controversies, like the work of Ancel Keys, mentioned by user @d8vewilliams: “And completely unnecessary unless you have fallen for the Ancel Keys lies.” Keys, a physiologist who pioneered the diet-heart hypothesis in the 1950s, linked dietary saturated fat and cholesterol to heart disease through his Seven Countries Study (web ID: 3). While his work shaped modern dietary guidelines, it’s been criticized for cherry-picking data—excluding countries that didn’t fit his hypothesis. This has fueled skepticism among low-carb and keto communities, who argue that the demonization of cholesterol and saturated fat may be more dogma than science.

The Complexity of Lipoproteins: Beyond “Good” and “Bad”

In a follow-up post, Harcombe takes her rant a step further, pointing out another layer of complexity: “If someone starts talking about cholesterol and then starts talking about small dense large fluffy LDL… they’re now talking about lipoproteins, not cholesterol.” She’s referring to the subtypes of LDL particles—small, dense LDL is thought to be more atherogenic (artery-clogging) than large, fluffy LDL. But her point is sharp: if the cholesterol hypothesis is really about lipoproteins, why are we still fixated on cholesterol itself?

This resonates with modern research. The TIME article (web ID: 0) notes that doctors no longer focus solely on total cholesterol levels because LDL and HDL behave differently. For example, familial hypercholesterolemia, an inherited condition affecting 1 in 200 people, causes persistently high LDL levels and increases heart disease risk. But for the general population, the picture is murkier. High HDL levels, once thought to be universally protective, don’t always guarantee heart health, and lifestyle factors like diet, smoking, and exercise play a huge role in lipoprotein levels (web ID: 1).

User @Brent_R_ adds a helpful analogy: “LDL taxis cholesterol to the cells of the body, primarily the liver, muscle, and adrenal glands. HDL is a garbage truck that transports cholesterol (and waste) back to the liver for processing & elimination. They work together.” This teamwork is key—LDL and HDL aren’t enemies; they’re part of a balanced system. Disrupting that balance with drugs or oversimplified advice might do more harm than good.

What’s the Alternative? A Call for Clarity and Skepticism

Harcombe’s post sparked a lively discussion on X, with users sharing their frustrations about the medical system’s handling of cholesterol and related issues. @WendyPuerto laments, “I asked my doctor about this & they didn’t have a clue,” while @KevinWa57956936 asks if a similar “scam” is happening with thyroid medication, pointing to a broader distrust of medical dogma. @Louis33s offers a radical solution: “STOP Consuming Carbs, Sugars, ALL Plants, and Processed Foods. The rest will take care of itself!!!” While extreme, this reflects a growing interest in low-carb, high-fat diets that challenge conventional wisdom about cholesterol and heart health.

So, where does this leave us? Dr. Harcombe’s rant is a wake-up call to question the cholesterol narrative we’ve been fed for decades. LDL and HDL aren’t “good” or “bad” cholesterol—they’re carriers, not cholesterol itself. The science of heart disease is far more nuanced than a simple blood test can capture, and the financial incentives behind cholesterol-lowering drugs deserve scrutiny. As @brotyboy puts it, “I need more rants like this.” And honestly, so do we all.

If you’re concerned about your cholesterol levels, don’t just take a prescription and call it a day. Ask questions. Dig into the research. Consider lifestyle changes—diet, exercise, and stress management—that can support your body’s natural balance. And maybe, just maybe, think twice before labeling cholesterol as the enemy.

What do you think? Have you or a loved one been prescribed statins or told to lower your cholesterol? Do you agree with Dr. Harcombe’s take, or do you think the “good” vs. “bad” cholesterol framework still holds water? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

This blog post summarizes Dr. Harcombe’s post, integrates reactions from other users, and provides context from the web search results, all while maintaining a conversational tone suitable for a health-focused audience. Let me know if you’d like to adjust the style or add more details!

Leave a Reply